MULTAN, Jun 22 : When the mankind galloped off on the road to modernism, many primitive values were trampled down knowingly or unknowingly, to be replaced by modern living and styles.

Some very noble and heart-soothing cultural and traditional values faded away with the passage of time entirely changing the lifestyle, overall social fabrics and even the family system.

Once used to maintain strong binding among communities in both rural and urban areas, many traditions have slowly been swallowed by modernity and inflationary trends. These customs not just cultural but a basis for emotional lifelines, are no more seen around.

From the ‘panchayat’ system to ‘saipi’ (barter) system, community living and many other dying beautiful traditions tell the story of a matchless cohesive rural life.

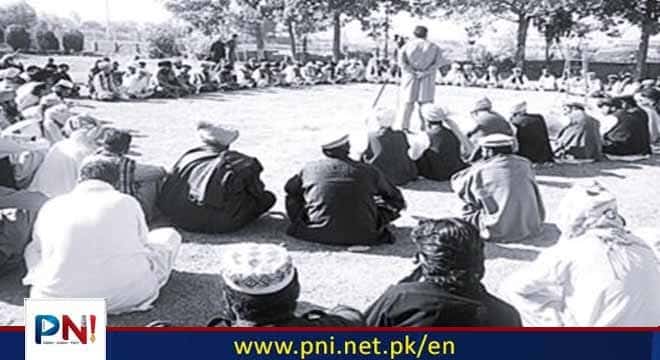

“Panchayat was a nice tradition of village life – an informal platform for dispute resolution by the elders at village level,” said Rao Liaquat, a social worker and political figure. “The panchayat was not about the law but a mode of collective wisdom to resolve disputes with consensus, honor and dignity.”

“It was more than a local court. It was the village’s conscience, saving locals from unnecessary litigation. But, it is no more there and today people spend millions of rupees with counsels at courts,” he remarked.

The grace of this system lied in its functioning. Comprised of respected elders, ‘panchayat’ used to gather at common place along with other villagers and local resolve the disputes like quarrels, fighting, boundary conflict, family misunderstanding or financial issues.

“There was no lawyer or a case like in a court or the paperwork,” Rao Liaquat maintained. “The decision of the elders was final and accepted with respect. It wasn’t always about punishing. But, reaching a settlement with dignity and harmony.”

This system not only used to resolve issues quickly and without any cost but also preserved relationships. Today, with its decline, minor matters often turn into long legal battles, draining time and resources.

Similarly, there used to be ‘Night Patrol’ by the youth who used to march or gather at important points of a village to guard the residents from thieves and decoits.

In an age when there were no CCTV cameras and private security, young men from the village used to take turns keeping watch during the night walking through streets often carrying batons and lanterns.

“We didn’t see it as a duty. It was a pride. We were guardians of our people. The village slept peacefully because we stayed awake,” shared a teacher Israr Kharl, recalling his youth days.

“That system created a deep sense of shared responsibility and bonding among youth and also trained them in discipline, unity, and leadership,” he said. “Sadly, this selfless tradition is now obsolete, replaced by individual concerns and security guards.”

Among the most fascinating systems was the ‘Saipi’ barter model, where tradesmen like barbers, carpenters, blacksmiths and potters offered year-round services and, in return, received grains or goods at harvest.

“We didn’t charge cash,” say Bashir and Haq Nawaz, senior barbers from Vehari. “We received respect, seasonal wheat and were treated like family members during weddings.”

Delivering wedding invitations was also a specialty of some barbers. They didn’t just carry cards but emotions of love and respect. “People gave generous gifts to the card-bearer,” recalls Haq Nawaz. “It was an honour. We used to feel immense pleasure after getting the gifts”.

Similarly, weddings were community events as there were no fancy halls or hotels. Tents were pitched in open fields or village streets. Friends and cousins assisted the cook and serve and arrange multiple shifts of food for guests.

“A wedding in a village was happy moment for everyone,” says Ahmed Nawaz Asar, a landowner. “There was no hired staff, only heartfelt services rendered by the local community.”

“Similarly, villagers themselves had to manage cots, chairs, bed sheets and residences for the guests. Guests of a house were considered as guests of the whole village,” said Ahmed Nawaz.

“During all seasons, there had been a central village tandoor (clay oven) where women baked large wheat breads,” he said. “Every women used to wait for her turn and it was not just waiting but also a source of chatting, humor, laughing and helping each other during baking of tandoori breads.

“Sharing food was another noble tradition. Curries passed over walls, lassi offered to neighbors and guests without formality and neighbors even sharing fodder for animals,” said Shaukat Khan Daha, c cultural enthusiast. “Today, people are restricted to boundaries and forgot the revered customs of the past.”

Another beautiful tradition of “Wangaar” was also common in rural areas. At times of sowing and harvest crops, construction of houses and other major activities, villagers helped each other cut crops or lend hand in other tasks without expectation.

“It was unpaid labor, powered by friendship. People used to help one another on turns,” says Shah Nawaz, a farmer. “It was glaring norms of collectiveness and cohesion at communities’ level.”

But, all these customs have slowly been replaced with individualism and modernism. People have sufficient money and avenues but not strong bonding collectiveness and cohesion.

Follow the PNI Facebook page for the latest news and updates.