N’Djamena, March 7 (AFP/APP): Younous Wakai Djimmy admits he felt a little unsettled when he set foot on the soil of his native Chad last August for the first time in 13 years.

He spent years in the arid wastes fighting the country’s iron-fisted president, Idriss Deby Itno, and then took the path of exile abroad.

Now the rebel is back home — thanks to a deal reached with Deby’s son and successor, Mahamat Idriss Deby Itno.

Deby, a 37-year-old four-star General took over at the helm of a junta last April after his father died from wounds sustained fighting insurgents in the north of the country.

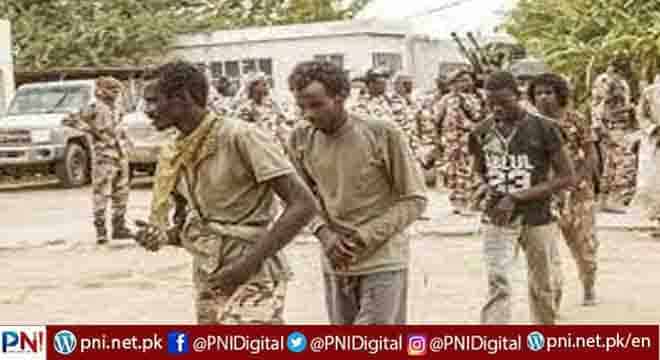

One of his earliest schemes was to extend an olive branch to fighters, allowing them to return home if they laid down their weapons.

The initiative is part of a plan for what the younger Deby calls an “inclusive national dialogue” to address the country’s many problems and chart the return to civilian rule.

Wakai Djimmy is a former leader of the Union for Forces for Democracy and Development (UFDD), one of the biggest armed opposition groups.

He joined in 2005, “when Chad was a dictatorship.”

When the offer of a return emerged last year, Wakai Djimmy swiftly contacted the authorities — “I want to give the new president the benefit of the doubt.”

An agricultural engineer by training, he is looking for a job, but says with a wry smile, “I don’t put my record as a rebel on my CV (resume) — that could discourage people from hiring me.”

His return and that of other rebels — several hundred, the government says — is causing ructions among former comrades-at-arms.

Deeply suspicious of Deby’s motives, hardliners accuse Wakai Djimmy of selling out for cash, and other returnees have been branded traitors.

“I haven’t touched a cent,” said Wakai Djimmy, telling his former comrades, “it’s time to stop this war so that Chad can advance.”

Another prominent ex-rebel is Kingabe Ogouzeimi de Tapol, 62, who just a few weeks ago was the spokesman for the Front for Change and Concord in Chad (FACT) — the Libyan-based group that launched the offensive that killed Deby’s father last April.

He spent 30 years in Switzerland, where he gained asylum and became a pastor, while at the same time carrying out duties for a succession of rebel groups.

Currently staying at a luxury hotel in N’Djamena, he came back in late January, and had a very public handshake with Deby — a meeting that led FACT to exclude him for “high treason and dealings with the enemy”.

Ougouzeimi’s response is that rebels should shift their strategy.

But he also admits he was ground down by exile, despite the “very good life” he had in Switzerland.

“It’s time to use other levers than war,” he said, adding emotionally: “I came back because I was unable to visit my mother’s grave — she died while I was in exile.”

The huge country has a long history of volatility since gaining independence from France in 1960.

It has a large but shifting constellation of rebel movements, of different ethnic affiliations and goals.

The elder Deby himself came to power in 1990 at the head of a rebel force which rolled into the capital.

In 2008 and again in 2016, columns of fighters came close to forcing him out in turn, but each time were thwarted by airstrikes by France, a close ally.

Kelma Manatouma, an expert on Chad at Nanterre University in Paris, said that by encouraging the homecomings the younger Deby seeks “to decapitate the armed groups, or at least divide them” — an allegation rejected by the government.

Deby has invited 23 groups to the national forum in N’Djamena in May, which is designed to set the country on course to “free and democratic elections.”

So-called precursor talks between the government and rebels were scheduled to have take place last weekend in Doha, the capital of Qatar, but have been delayed. The latest date for starting them is now March 13.

Despite the accusations against them, some returnees argue Deby’s death is a chance to turn the page.

One such voice is that of Mahamat Doki Warou, a former political advisor to the Union of Resistance Forces (UFR).

After returning in August, he met with the younger Deby, who appointed him speaker of the transitional parliament — a body set up by the junta to replace the previous legislature, which was dissolved.

“I had big differences with Idriss Deby, but I’ve got nothing against his son, and I want to give Chad a chance to end these years of war,” he said.

Follow the PNI Facebook page for the latest news and updates.